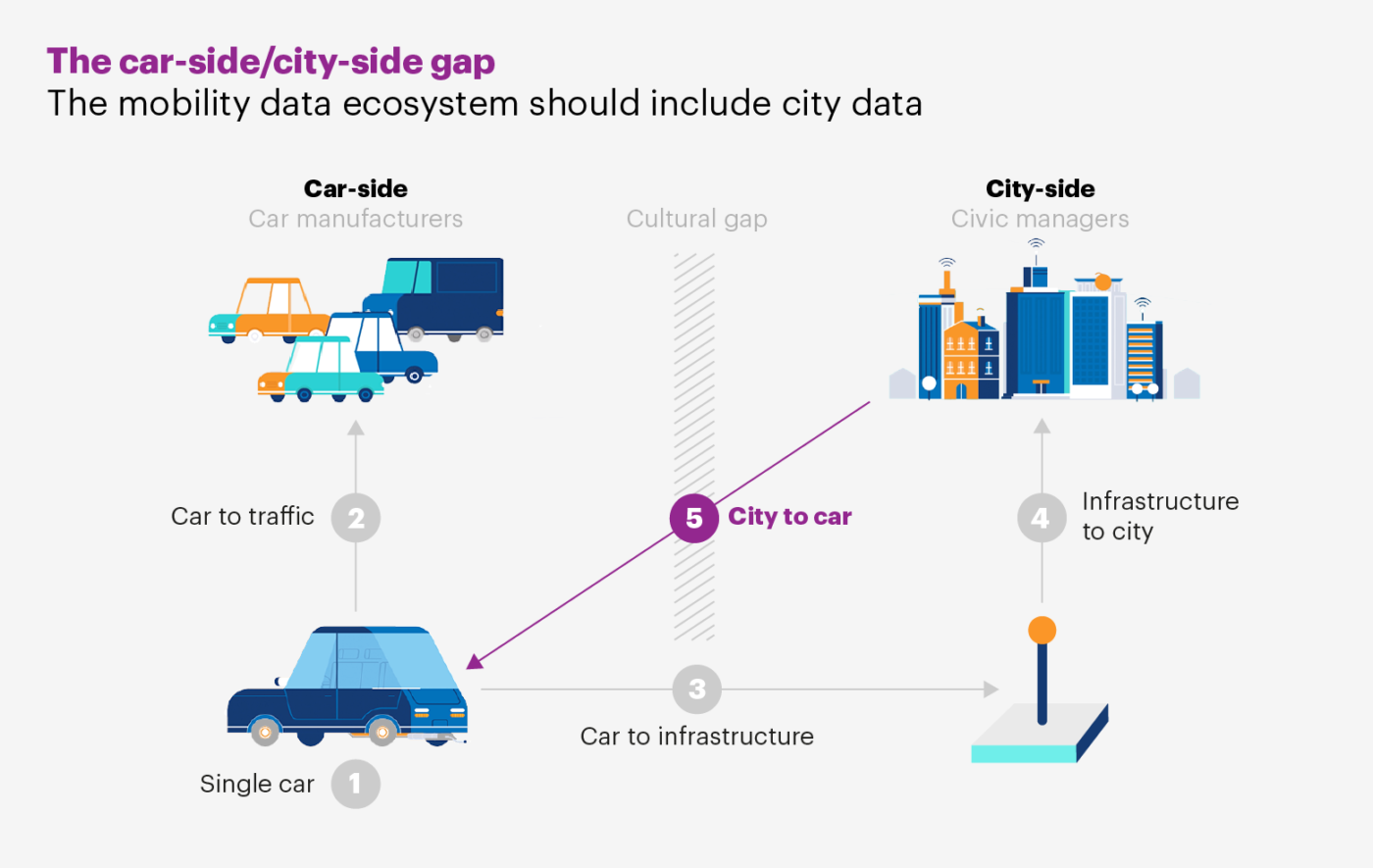

Car companies and cities need to work better together, especially in data sharing and collaboration in new service development, and the best way forward is an experimental approach. In light of this, we have developed a new framework, the car-side/city-side gap, which highlights the opportunity for better relationships between car manufacturers and cities.

Background

Our framework is based on the established financial services framework of the buy-side and sell-side in equities trading.

The framework

Carmakers and cities currently have very divergent strategies.

Car-side

At the micro-level, the car-side constitutes a single driver in a car. At the macro level, the car side makes up many cars within the same location.

For car manufacturers, the main priority is on sales; selling new cars ensuring they are offering new benefits for the driver.

City-side

On the micro-level, a city-side structure refers to single parts of connected infrastructure or vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) services. At the macro/largest level is the patchwork of infrastructure and services that make the whole city. (We’ll do other articles that position the smallest unit of the city as the citizen!)

For city authorities, their main focus is on the well-being of their citizens and the efficiency with which they are running the city.

Flows of value in the system

In addition to the framework nodes, there are five primary value flows as follows:

- The car is connected to services such as repair alerts for worn parts. These services benefit the drivers and owners of vehicles, allowing them to make more informed decisions about their vehicle and energy usage.

- A connected vehicle communicates with other vehicles on the road. For instance, when monitoring for collision detection, the single-car passes immediate benefits to the drivers of all vehicles by making the road near it safer.

- Smart infrastructure can detect vehicle activity, send and collect data from the car, or provide connectivity to connected entities such as cars. Mobility services are supported by this hardware and connective technology just as the wires under the oceans power the Internet.

- As individual smart infrastructure objects communicate with the city’s mobility database, the city may use its own infrastructure, satellites or other connectivity vendors to serve and collect data.

- Ideally, the car can access data held by the city or private suppliers who partner with cities. The car could receive advice on routing at peak travel times but could also send some of its telemetry data back to the city through satellite or smart infrastructure connections, thus contributing to a city analytics platform or ‘Intelligent Transport System’ for the benefit of other drivers and users of mobility services.

The gap

We see a gap between carmakers and city authorities, with our solutions bridging the gap between the history, culture and even resources of carmakers.

Carmakers often fail to develop services that benefit the city . There are four main reasons:

History:

Cities have existed for several thousand years. Mass car-ownership is just over a century old, with car usage influencing urban planning and existing in an uneasy peace with planners and authorities. City officials, on the other hand, think about the mobility of the whole population, not just car owners.

Culture:

Car companies are led by engineers who closely guard innovation in invented IP and patents as their competitive edge. This breeds a competitive mindset and one that is suspicious of outside collaboration. Cities are run by public servants who are often suspicious of the motives of corporations.

Data non-operability:

City and mobility data comes from a variety of sources and is diverse and challenging to work with. The ecosystem is complex. Car companies and cities often do not have experience in data ingest, analytics, and service development.

Resources:

Both city finances and carmakers’ profit margins are being squeezed at this stage in the early 21st century. Cities everywhere face steady growth that is not matched by funding. Car companies face the triple budgetary challenge of powertrain electrification, implementing autonomy, and falling demand, not to mention volatile macroeconomic headwinds and trade wars.

Solutions

One solution can be found in running experiments that borrow the best ideas from technology startups while respecting the complexity of bridging the car-city gap.

An experimental approach will entail prototyping new services. This work would involve:

- Creating conditions for stakeholders to agree on what value they are seeking to create.

- A way of measuring the experiments and communicating these outcomes.

- Balance in city experiments is crucial. Include enough dependencies to make the project realistic, but not enough so as to make the experiment too unwieldy.

- Work with city partners, not just with your internal teams. Without access to how they work, you will not create any lasting value.

- City partners should seek to create temporary experimental zones. For instance, experimental traffic management orders can legislate for temporary changes in the public realm without the need to wait for new policy or legislation.

- Cities are a complex regulatory/ legal environment, especially when using personally sensitive and/or commercially valuable data. For this reason, make sure your lawyers are available and briefed as the project develops.

One solution can be found in running experiments that borrow the best ideas from technology startups, while respecting the complexity of bridging the car-city gap.

Summary

One of the biggest barriers to effective mobility projects is the car-city gap. This understandable gulf between stakeholders can be bridged with an expedient and experimental approach.

We will be writing more about expedient mobility experiments over the next year.

If you would like to know more get in touch.