The pace of new technologies, business models and startups often outstrips the social, civic, and municipal contexts—and smart mobility is a great example of this.

Challenges intertwined with smart mobility such as congestion and emissions are global and complex. If they remain unaddressed, these challenges that affect the business in a number of ways, for example:

- Cities lack appropriate smart city infrastructure, including lacking budgets for developing data services.

- Cities do not have access to robust evidence, making data-informed decisions hard to make.

- Cities lack the ability and resources to develop data services themselves, and so need to work with corporate partners, who in turn need to work with the cities to create markets for their products.

Smart mobility landscape

To consider smart mobility as a subset of the smart city is to recognise a complex landscape of business, government, regulation and citizens, facing an abundance of services vying for their attention.

When layers of the smart mobility landscape become fragmented or are treated in isolation, problems arise for each of these groups. For example, Uber’s challenges with city zoning laws and infrastructure capacity. Autonomous cars will require testing in allocated and prepared parts of the city, rather than being rolled out at once. New energy sources transforming cars on the street need integration with existing power and energy supply chains.

With data at the heart of smart mobility services, many companies are choosing to create new services as a competitive advantage. While we would not suggest an open data policy (see later recommendation on partnerships); a shared data policy with sound legal instrumentation would help everyone from citizens to corporations.

First of all, what (or who?) do we mean by the city?

We identify (and define) the city as a holistic, conceptual model of city leaders, civic managers and citizens.

Understanding city leaders is crucial because they are responsible for new initiatives, increasingly evidenced on data.

City civic managers such as parking officials who oversee the implementation of new schemes and the day-to-day running of the city also have an important role to play as users of digital services.

Civic leadership should bear in mind citizens who will be the benefits of services and also the recipients of any downside created by them.

Smart mobility service developers should design with these actors in mind and by extension—successfully work with the city.

Recommendations

In our work across the transport and aviation sectors and with cities, we’ve developed four recommendations for developing commercially successful mobility services, with lasting civic and financial value to the city.

1. Citizens first

Cities should think of their citizens as a group with diverse concerns and understand them with the needs of the whole community in mind.

Technology start-ups often act in competition with each other for the attention of single users. This means that while Uber is a great service for single customers, it can harm the citizenry as a whole due to the congestion caused by tens of thousands of Uber drivers, circling and waiting for work.

“The relentless focus on ‘the user’, which has driven so much product and process improvement over the last two decades, is also the blindspot of the digitally-oriented design practices. They can only look up from the homescreen blankly, through the narrowly focused lens of ‘the user’, when asked to assess the wider impact of such services when aggregated across the city.”

From The City is my Homescreen, Dan Hill, Director of Strategic Design at Vinnova

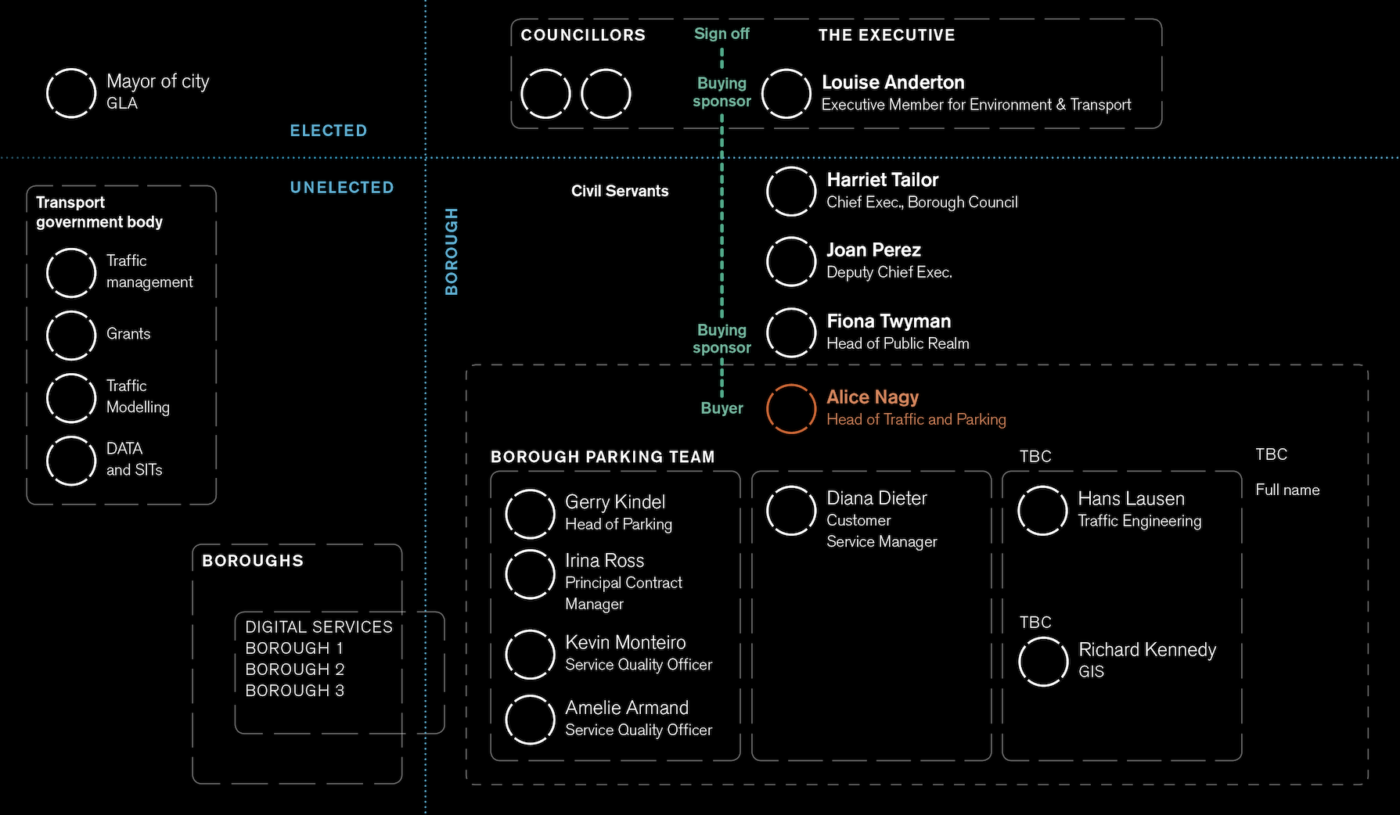

2. Mapping users of Smart Mobility services

Using corporate cartography that shows the connections between city stakeholders is an important tool when mapping users of smart mobility services. As part of user research, whether on city stakeholders or chief executives, we recommend teams develop visual maps that highlight the entire user network as well as single users.

Creating a visual diagram shows how personas share information, who makes and uses the data and levels of decision-making processes.

A corporate cartography exercise demonstrates project stakeholders, in addition to demonstrating possibilities for the design team, an overview of how service development can assist with information flow, compliance problems, service ownership and maintenance.

3. Design in collaboration with lawyers

Among the most important people in a city mobility project are lawyers or solicitors. We recommend smart mobility teams ensure regular access to lawyers, not just through the city or client team counsels, but also through their legal resources that can be commissioned alongside any project. Due to the complexity of city mobility projects, many services will eventually require new contracts for data or between stakeholder groups.

With lawyers readily to hand, it is possible to create draft instruments and new contracts quickly around data ownership for testing zones or temporary traffic schemes. This can avoid waiting around for months. Designers can create a brief for lawyers, including schematics of user needs, data needs per group and prototype contracts alongside other service design assets.

“A good legal advisor should be seen as a natural extension of your commercial team. They should be helping to bring value to a commercial venture, whether that is through unlocking additional value within the deal itself or helping to protect you against any fallout further down the process.”

Jamie Smith, Sheridans

4. Create robust and valuable data partnerships

At the 2019 Financial Times ‘Future of the Car’ conference, Michael Hurwitz, Director of Transport Innovation at Transport for London, said that private companies are generally poor at sharing the data they create.

The opposite end of the spectrum is open data programmes that only exist for as long as they have an executive sponsor in a city. We propose a middle ground where city data is created with different licensing models, assuming it will be combined and benchmarked with other data within and across other cities.

This allows the creators of the data to preserve a degree of commercial IP while also sharing it for mutual benefit. Thorough legal instrumentation is required to make these deals work.

Designing mobility services well today ensures citizens needs will be met tomorrow.

Striking a balance between experimentation and genuine citizens’ needs is critical. Thorough user research frameworks, an experimental approach and a well-formulated legal framework can support designers in doing so. These methods can uncover challenges and risks but also nuances and an understanding of what should be developed.

With the city in mind, smart mobility service developers will have a sound framework for commercial longevity, profitability for their business and a valuable service for their citizens.